On Wednesday, May 9, 1979, mourners gathered at St. Paul of the Cross Catholic Church in west Atlanta. They came from throughout the country, most of them from the family of professional baseball, many with names already indelibly writ in the sport’s history books, some to be enshrined eventually in the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. The man whose life we had come to honor was forty-three and not broadly recognized by the general public.

Bill Lucas died too young to be remembered for accomplishments in terms of records. Still, he had lived long enough for Florida A&M football coach Jake Gaither to gather his emotions and call Lucas “one of God’s great men.” That was reason enough for most of us to be there, for he was loved more as a good and honorable man than as general manager of the Atlanta Braves.

I don’t recall any speakers mentioning that Bill Lucas was the first African American to be named general manager of a Major League Baseball franchise. It would have been natural to do so, since America was only eleven years distant from the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. But Lucas had advanced so meritoriously into his position that to mention he was a pioneer might have diminished what he had earned purely with baseball savvy and reliability. Lucas’s boss, Ted Turner, famously color-blind but stunningly inappropriate as a speaker, rendered a eulogy peppered with cliches: “Now Bill is the general manager of a team that has Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, and Lou Gehrig . . .” Fortunately twenty-three-year-old Dale Murphy restored dignity with thoughts about how Lucas, first as farm director and later as general manager, had become a father figure, a symbol of what it means to be a professional baseball player. “Bill’s dream was for this organization to be a success. It is our sacred honor to be chosen to fulfill his dream.”

By the time Turner promoted him to general manager in September of 1976, Lucas had spent almost twenty years in the Braves organization, six of them as a minor league player. Lucas had the slender build of a middle infielder, the speed and guts of a base stealer, and a respectable .273 batting average. But a knee injury at Double-A suddenly left him better suited for mentoring. In 1965, as the Braves served a one-year injunction that prevented the team from moving to Atlanta from Milwaukee, vice president Dick Cecil convinced Lucas, a graduate of Florida A&M, to join the front office in a community relations role.

The Braves’ arrival in Atlanta required sensitivity to the city’s complex racial environment. Cecil knew Lucas would bring crucial perspective to the relationship, as would his former minor league teammate Paul Snyder. Years later Snyder reflected on Lucas’s 2006 induction into the Atlanta Braves Hall of Fame: “A number of places in the Texas League, where we were playing in 1962, Luc couldn’t sleep in the same hotel we did. He couldn’t eat in the same place we did. A lot of nights, we’d bring food down to him in the bus. A lot of nights, he’d sleep in a boarded-up hotel downtown . . . He just buttoned his lip, went out and played his heart out.”

When I joined the Braves’ front office prior to the 1966 season, Cecil, Lucas, Snyder, and others had already planted baseball’s unique seeds of emotional unity in a city where relationships previously had been forged from mutual economic interests. Those men initiated the Braves’ Good Neighbor program in underserved areas, providing athletic fields, equipment, leadership, and whatever else was needed to underscore the Braves’ appreciation for their welcome. Lucas helped Cecil bring the same attitude to building a workforce for Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium. He systematically hired one African American for every white person selected.

Lucas remained resolutely sensitive to inequality over his fourteen years in the executive suite. In the summer of 1972, my last season with the Braves, Atlanta hosted Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game. Gender fairness had yet to chip away at baseball’s chauvinistic armor. Lucas was on his way to one of the glamorous event parties when he met up with Susan Hope, wife of public relations director Bob Hope. She had been turned away at the door of the all-male event. Lucas took her arm. “Let’s go have a drink,” he said. When Susan explained she wasn’t allowed, Bill said, “Look, my people weren’t allowed to enter nice places for years either. Come on, someone’s got to be the first woman to integrate baseball.” And so they did.

When Turner hired Lucas as general manager in 1976, the Braves had come off of two of the most disastrous seasons in Atlanta franchise history, losing 194 games. Lucas set to work immediately, hiring young players who would eventually win the Western Division championship in 1982. In 1978 Lucas tapped Bobby Cox to be manager, choosing the future Hall of Famer from a list that included Yogi Berra and Dick Howser.

By 1978 the strain of maneuvering through minefields strewn with Turner’s quixotic decisions began to exhaust Lucas. Increasingly, he had to defend his reputation for ironclad integrity. After Lucas and Phil Niekro verbally agreed to terms of a new contract, Turner balked, offering Niekro substantially less. Niekro asked to be traded but finally signed for three years at $200,000 annually.

That same year, Lucas drafted University of Arizona second baseman Bob Horner. Horner became an instant star at third base. The National League writers named him Rookie of the Year. The next spring, Lucas once again found himself in the middle of a salary dispute. Horner’s agent, Bucky Woy, claimed that Turner wanted to pay Horner some $83,000 less than he made his first year if the signing bonus were included. Woy publicly called Bill Lucas a liar, saying Lucas had offered a suitable contract earlier.

Early on May 1, Bob Hope overheard Turner and Lucas in “a verbal brawl” over how the deal with Woy was progressing. After work, the weary Lucas went home to watch a Braves game televised from Pittsburgh, where Phil Niekro won his 200th game. Lucas telephoned congratulations and told the pitcher to have a celebration on the Braves’ tab. Shortly after midnight, Lucas collapsed. On May 5, he died without gaining consciousness, victim of a massive cerebral hemorrhage.

Four days later, hundreds gathered to celebrate the life of a man who would never become widely remembered as a picturesque national figure; pioneering, after all, isn’t always about writing your own script. It might be said, in fact, that Bill Lucas’s brief life was almost a one-act play. In a broader, lengthier tale about Atlanta, the star of Lucas’s widow, Rubye, would eventually rise as her husband’s would have. She would be appointed to the board of directors of Turner Broadcasting in 1981. (She was one of only six directors formally approving the sale of Turner Broadcasting System to Time Warner in 1995.) She would become president of the William D. Lucas Fund that sends deserving young baseball players to college. She would raise funds for the NAACP and United Negro College Fund.

At a 2009 reunion of the original Atlanta Braves front office family, appropriately arranged at Manuel’s Tavern, I chatted with Rubye for the first time in years. Rubye was radiant and smiling, as old friends exchanged handshakes and hugs, trying to fit missing pieces back into a mosaic of memories. There was little doubt Bill would be proud of the woman who remains so proud of him, a man who had epitomized the very change he wanted to see in the world.

This article originally appeared in the May 2011 issue.

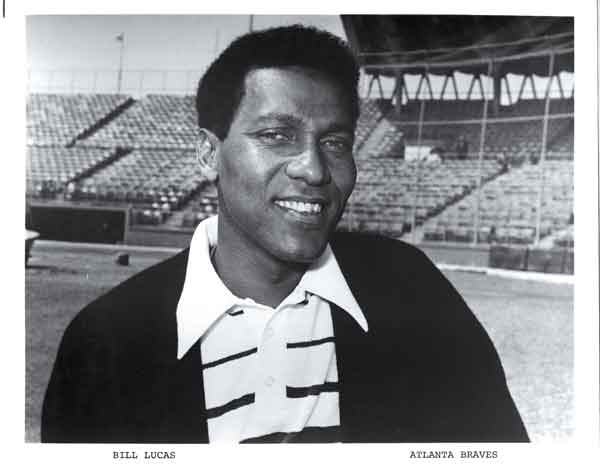

Photograph courtesy of the Atlanta Braves